Clemens Scherzer, a physician-scientist and leading researcher on Parkinson’s disease, has amassed a somewhat unusual collection: one million brain cells and 300,000 sample tubes of DNA, RNA, microRNA, plasma, serum, spinal fluid, and cryopreserved cells. The biospecimens were contributed by 4,000 study participants suffering from Parkinson’s disease as well as by people without the disease for comparison. In January, Scherzer was hired from Harvard to direct the new Stephen and Denise Adams Center for Parkinson’s Disease Research at Yale. Here, he is scaling up his work, with the goal of mapping a total of six million brain cells and enrolling one thousand additional patients in his study, now named the Yale-Harvard Biomarkers Study and Biobank. With copies of his biobank at Yale and Harvard, Scherzer is making his data accessible to scientists around the world to accelerate Parkinson’s research globally.

With generous funding from Stephen Adams ’59 and his wife, Denise Adams, Scherzer hopes to identify treatments that slow or stop the disease. Parkinson’s disease has proven difficult to treat in part because scientists and doctors still don’t know exactly what causes it. Its symptoms—including tremors, slow movements, and cognitive problems—were once thought to be confined to the brain, but Scherzer and other researchers have since discovered that molecular changes can be detected in the blood stream and cerebrospinal fluid, too.

Scherzer says that most Parkinson’s treatments are “reactive,” meant to treat symptoms rather than stop the disease itself. “We’re on a mission to develop precise, preventive medicine that allows us to predict the disease progression in a patient and make the minimal needed intervention,” he says. “We’re now able to harness next-generation genomics and powerful artificial intelligence to find potential cures for this disease that affects more than ten million people.”

Scherzer and his collaborators at the Adams Center are building what they call the Parkinson DiscoveryEngine, a molecular map of the disease created by using the extensive biobank that Scherzer has amassed alongside AI to search these data. “We can model how different genetic variants change gene activity in brain cells and learn to predict and prevent disease progression in patients,” Scherzer says.

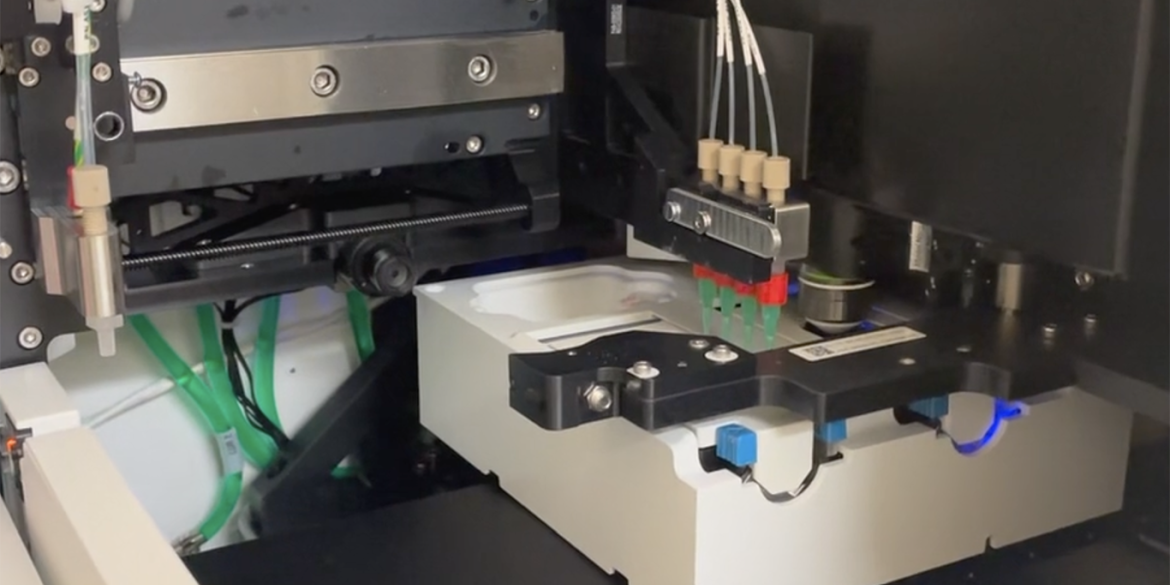

Another cutting-edge technology in the new center is the Xenium Analyzer, a spatial transcriptomics instrument that can map which genes are expressed in specific cells in brain tissue at high resolution. The video below shows Xenium in action.

Scherzer expects his work to lead to the development of medications and partnerships with pharmaceutical companies. But the National Institutes of Health and other grant-making organizations usually fund research on the mechanisms of disease and to identify genes, while pharmaceutical companies are eager to collaborate with researchers to bring drugs to market only after they’ve been shown to be effective. “There’s this ‘valley of death’ between the discovery of a new gene or drug target and successful proof-of-concept drug trials. That’s where philanthropy is crucial,” Scherzer says. “We need visionaries like Stephen and Denise who are willing to take on that risk and provide support.”

Old Drugs, New Uses

In addition to his work developing new drugs, Scherzer also screens existing drugs for unrelated conditions to see if they could be repurposed as treatments for Parkinson’s disease. This approach has already identified a surprising candidate: asthma medications. The active chemicals in many asthma inhalers seem to reduce the body’s tendency to produce a protein that accumulates in the brain of people with Parkinson’s. Overall, people who took these medications were less likely to develop the disease. Phase 2 clinical trials to test some of these compounds have shown promising results.

Stephen Adams ’59: A Foundation of Giving

Stephen Adams passed away a few months before his 65th reunion, where classmate Richard Lightfoot ’59 spoke in tribute to Stephen and his wife Denise Adams. “For more than thirty years, Denise and Steve have combined to share their good fortune,” Lightfoot said. “They merit the thanks from a grateful university and those who benefit from their generosity.”

Adams’s son Kent also spoke at the reunion. “My father felt gratified and proud to help others,” he said. “He put his thoughts and resources behind what was important to him.”

Charles Ellis ’59, a friend of Adams and one of the class gift committee chairs, was impressed by his business and financial achievements. “But what’s in some ways more impressive is that through all of that, Steve was just a really nice guy,” Ellis says. “He liked to do things that were significant in his quiet way.”

The class raised $50 million for their reunion, the third largest 65th reunion gift total in Yale’s history. Edward Greenberg ’59, the other class gift committee chair, notes that Adams was a crucial part of that. “He provided the foundation for it, and we built the rest.”

“An Incredible Urgency”

The longstanding generosity of philanthropists Stephen and Denise Adams has had major impacts across the university. Their donation in 2006 allowed the Yale School of Music to become tuition-free, and the Adams Center for Musical Arts was named in their honor for further support of the school. The couple is also providing funds for the new Adams Neurosciences Center at Yale New Haven Hospital, which will collaborate with Scherzer and his colleagues. Stephen Adams suffered with Parkinson’s for many years; he passed away earlier this year.

“Stephen and I are both humbled and overjoyed by the privilege of supporting both the Yale School of Medicine and the Yale New Haven Hospital in finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease,” Denise Adams says. “Together, these two collaborative institutions are aiming to be a destination in the world for finding a cure and treating neurological diseases. Our hope is that this effort will be a beacon of light to many who suffer.”

Yale is ideally positioned to make rapid, meaningful progress in treating Parkinson’s, Scherzer says. “Yale has an amazing community of ingenious scientists, engineers, and physicians who are all coming together to solve Parkinson’s disease,” he says. Yale is the only institution to have multiple concurrent grants from Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s, a global research initiative, including one supporting Scherzer’s work at the new center. In 2024, Yale was recognized by the American Parkinson Disease Association as one of its nine national research centers of excellence.

In addition to his research, Scherzer is a physician who treats patients with Parkinson’s disease. “Every patient is a reminder that we are running out of time,” he says. “We need to work as quickly, as efficiently, as possible. We feel an incredible urgency to do that.”