There are millions of reasons (and counting) to love Yale’s new cross-collections information system, LUX. Launched in June, LUX provides access to the full breadth of Yale’s cultural and natural history collections through one portal for the first time. The web-based platform is free to use and encompasses more than forty million records from the Yale Center for British Art, the Yale University Art Gallery, the Yale Peabody Museum, and Yale University Library, which includes the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the Lewis Walpole Library, and specialized collections devoted to the arts, music, film, history of medicine, and religion.

Previously, no easy method existed for searching Yale’s museum collections together with its library collections or for discerning associations among objects within different collections. Now LUX enables researchers to use simple language to discover art, cultural, and scientific heritage objects across Yale’s holdings and to explore the robust networks of relationships among them without prior knowledge that any ties exist.

A New Standard for Cultural Heritage Collections

The project, which has been in the works for five years, involved input and expertise from nearly one hundred staff members across Yale’s collecting institutions and the Information Technology Services department. The monumental effort was made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, in addition to funding from the university.

“LUX represents an important milestone in Yale’s ongoing collaborative effort to improve access to our natural and cultural heritage collections for a global audience and to support teaching, learning, and research with collections at Yale and around the world,” says Susan Gibbons, vice provost for collections and scholarly communication.

“It’s a game-changer for the cultural heritage domain,” adds Robert Sanderson, Yale’s senior director for digital cultural heritage. “No other institution has a system with this level of capability. It shines as an example of unique digital innovation and has attracted enormous interest from peer organizations who are keen to replicate it for their own collections.”

Open access has long been a hallmark of Yale’s cultural heritage collections strategy. As such, the team behind LUX designed much of the platform to be shared openly and broadly, including its software, processing architectures, user interface, and metadata, to make it easier for other institutions to build their own versions of this groundbreaking tool.

“We want our collections and knowledge to benefit the world—and that includes our digital infrastructure,” Sanderson notes. “It’s essential to our educational mission that we ensure LUX is not a Yale-only product. Sharing our expertise and building a community around access, transparency, and standards is a fundamental part of our approach to cultural heritage.”

LUX at a Glance

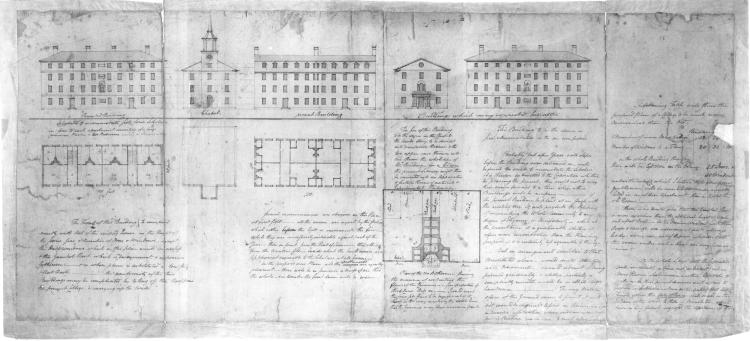

Using LUX, a search for “John Trumbull” (the artist who rendered many of revolutionary America’s defining moments and who established the Yale University Art Gallery in 1832) pulls up, from across Yale’s different collections, 680 objects Trumbull created or owned or that are otherwise related to him.

Tabs located above the primary search field direct the user to “works,” “people and groups,” “places,” “concepts,” and “events” relating to Trumbull, each revealing new avenues to investigate. An advanced search function for targeted queries allows users to go even deeper.

Illuminating What’s Possible

While it is already a powerful tool, LUX remains a work in progress. With future support, Sanderson and his team look forward to expanding its functionality and adding data sets from Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage and the Paul Mellon Centre. Beyond that, LUX could also be linked with databases from other institutions. As it grows, LUX promises to further revolutionize how students, scholars, and researchers across the globe access and engage with collections as they seek answers to new and timeless questions.