“There are eight billion people on this planet now, and each of us is in a very specific place in a very specific geographic context,” says Jennifer Marlon, the inaugural executive director of the Yale Center for Geospatial Solutions which launched in early 2024. The problems facing the world today are multitudinous and interconnected, but a solution appropriate for one location may not work in another. Context matters.

“It’s only within the last decade or so that we are able to get the data to understand those contexts,” Marlon adds. “With smartphones, with satellites, and now with AI, we are in the midst of a data revolution, and it’s transforming the kinds of questions we can ask. The new center can help ask, and answer, some of those questions.” Marlon has spent the last decade as a senior research scientist and lecturer at the Yale School of the Environment (YSE). She has also served as the director of data science for the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Geospatial data can come from many sources, including space-based observations, ground-based sensors, smartphones, and citizen science projects. At its core, geospatial research is the science of “where,” says Karen Seto, a co-director of the new center and the Frederick C. Hixon Professor of Geography and Urbanization Science at YSE.

“So many issues that we deal with today—climate change, biodiversity loss, pandemics—are about location,” she says.

Using geospatial technologies, researchers can connect regional or global occurrences to the hyperlocal human scale, says Marlon, such as the Canadian wildfires that led to hazardous air quality hundreds of miles away in New York City and the COVID-19 pandemic. “Global links are connecting us all,” she says. “Now we have the data and the analytical tools to examine and analyze those connections.”

Costas Arkolakis, the center’s other co-director and a professor of economics at Yale, agrees. “The center will help us examine geospatial data at different scales,” he says. “What we could do for a small sample, now we can do for the globe. And what we could only do for a large region before, now we can do for a neighborhood.”

Consolidating Fragmented Expertise

Often, researchers working with geospatial data use geographic information system, or GIS, software. Yale has a strong foundation in geospatial research, teaching, and facilities, including a GIS librarian and the Earth Observation Lab, which provides powerful computers, software, and expert assistance. But these resources are fragmented across the university, Marlon says. The Yale Center for Geospatial Solutions (YCGS) will bring together these resources and reduce redundancies while expanding Yale’s capabilities through hiring new faculty, acquiring new computing hardware, and integrating support services.

Faculty and staff from ten professional schools, Yale College, and other existing centers—including the Yale Biodiversity and Global Change Center and the Yale Center for Business and the Environment—will come together to make up the center.

“Yale has some of the world’s top experts who use geospatial data,” says Seto. “That existing expertise means we’re not starting from scratch, so we can have a significant impact quickly.”

Guided Goals

The new center emerged out of a recognition of the importance of geospatial technologies to answer some of the globe’s most pressing questions. It is one of several initiatives under Yale Planetary Solutions, an initiative that seeks to marshal Yale’s excellence and expertise to provide answers to climate change, biodiversity loss, and threats to human health and well-being.

Soon after its inception, YCGS hosted an inaugural faculty symposium to introduce the center’s resources to Yale researchers. The center’s leaders also facilitated discussions to help guide the focus of the center to best suit the needs of faculty and staff.

“One of the major roles that this center is aiming to play is supporting individual researchers who are already doing this kind of work, enabling them to work more efficiently,” Arkolakis says, citing faculty including Eli Fenichel at YSE, Juan Lora at Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kai Chen at the Yale School of Public Health, and Jodi Sherman at the Yale School of Medicine.

In addition to supporting the work of faculty and staff at Yale, YCGS aims to generate tools useful to both the public and to lawmakers and other decision-makers, Marlon says. The COVID-19 dashboard created at Johns Hopkins, for example, helped policymakers and the general public stay informed about COVID-19 hotspots. Marlon envisions creating similar dashboards and interactive maps that can support resilience at local to global scales.

Artificial intelligence will also play a role, turning satellite and spatial data into information that can be understood by anyone. AI is not only providing the basis for informative chatbots, however, it is also being used to leverage remote sensing observations in economic models, to analyze policy effectiveness, and to identify new opportunities to build more sustainable cities.

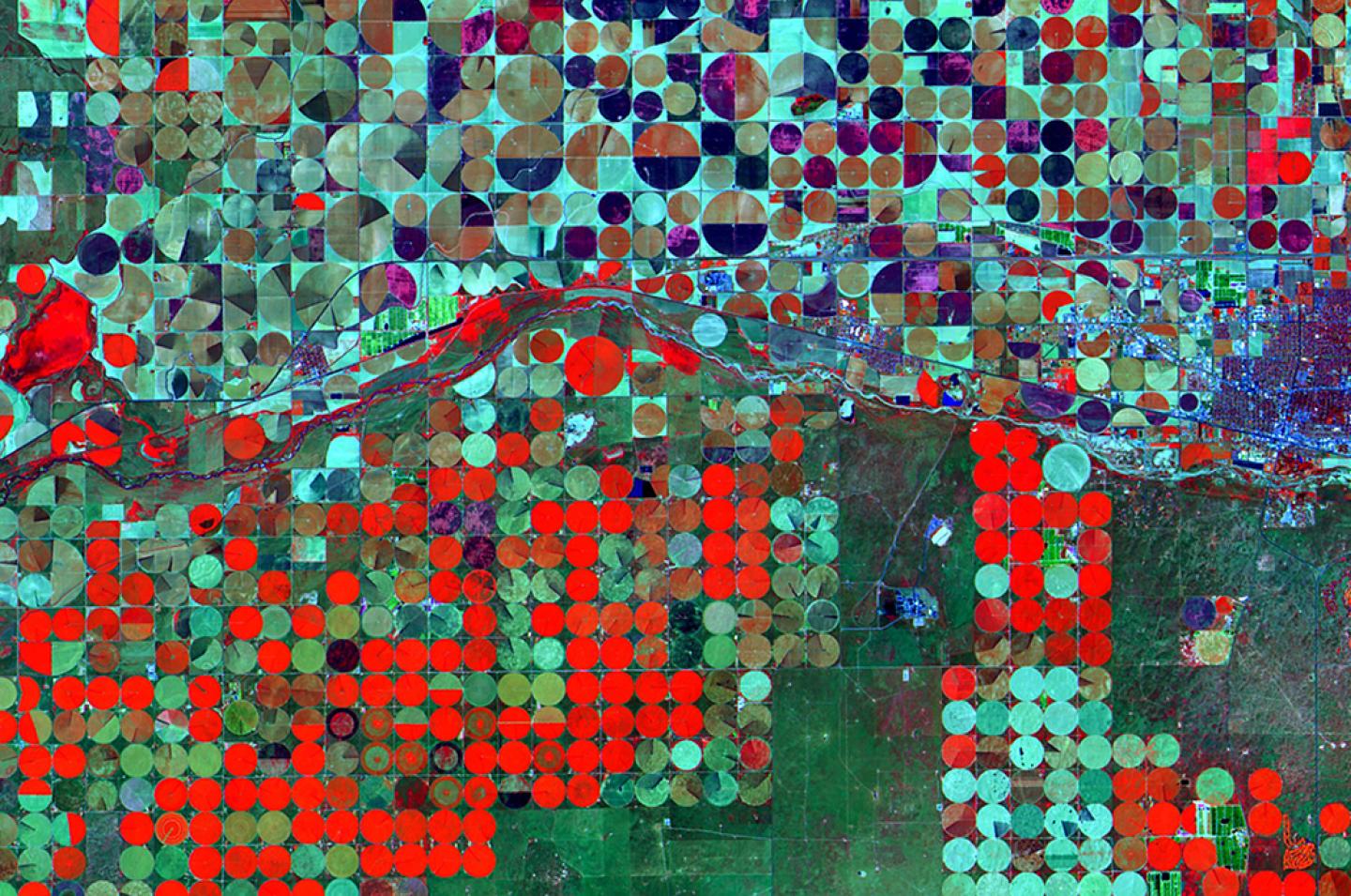

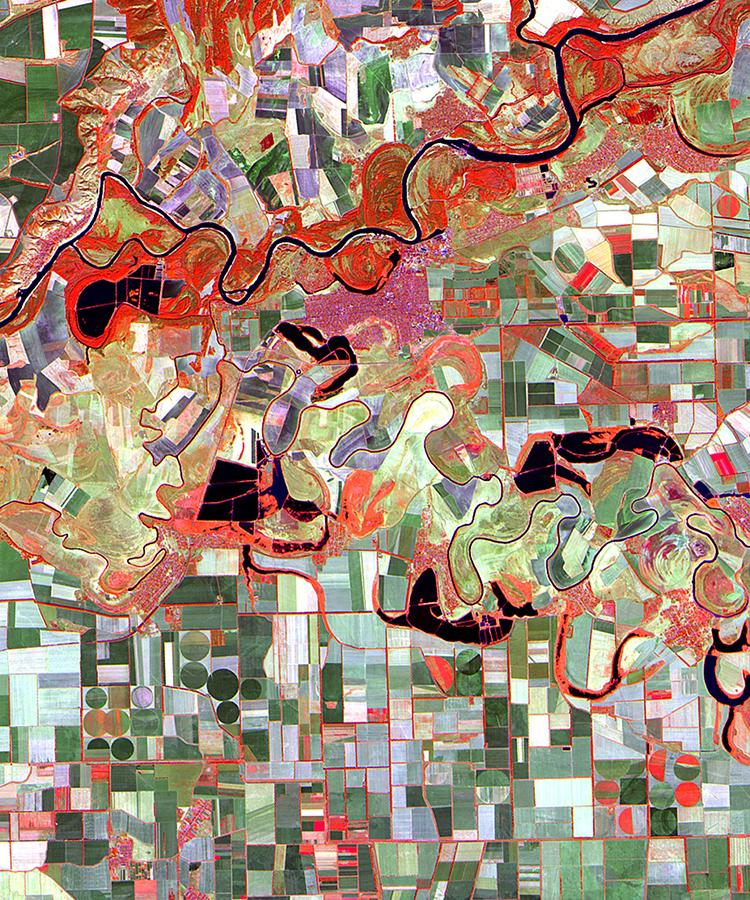

“The microscope transformed what we could see and created the kinds of questions we could ask and answer,” says Seto. “We’re in a similar time now with geospatial data, especially imagery from space. The large volumes of satellite data are changing how we see the planet, and in turn allowing us to ask totally new questions about humanity.”

Image credit for above image and header image: City Unseen: New Visions of an Urban Planet, by Karen C. Seto and Meredith Reba, 2018.