More than 80 percent of architects in the United States are white, and three quarters are male, making architecture one of the least diverse professions, according to the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards.

Billie Tsien ’71, a New York City-based architect and visiting professor at Yale who has led projects like the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, hopes that improving access to architecture education will help change those numbers.

Sharing that goal, Tsien’s longtime business partner Tod Williams has created a full scholarship at Yale School of Architecture (YSoA) in her honor.

“Leaving architecture school with tens of thousands of dollars in debt and going on to make very little money for many years is a frightening commitment, especially for people from underrepresented backgrounds,” Tsien says. “But not only is making architecture more diverse the right thing to do, it’s a necessity. Architecture cannot be successful without people from different perspectives and backgrounds.”

Honoring a Role Model

Tsien began working with Williams in 1977 and founded their architectural practice, Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, in 1986.

“Improving accessibility for architecture education is of utmost importance, and I am proud that this scholarship will allow more students to attend this incredible institution,” Tod Williams says. “Billie’s influence has not only been crucial to our firm’s success, but her dedication to making a better world through education, mentorship, and finding the humanism in architecture makes her a peerless role model for any aspiring architect. She epitomizes the values of YSoA and, in my opinion, there is no one more deserving of this honor.”

Tsien says she is filled with gratitude for the gift in her name.

“Tod and I have worked together for forty-six years, and we share a deep admiration for YSoA, where we have both taught for a long time,” Tsien says. “There is a uniquely humane culture here, where everyone works to learn from each other rather than ruthlessly compete. We take care of each other, so I am very moved by the idea that it will be easier for talented students to access this education.”

Seeking Out New Perspectives

This September, Tsien’s course at YSoA brought her and her students to the rainforests of Sitka, Alaska, where they worked on proposals for a new building at Outer Coast, a school that teaches through indigenous ways of learning.

The school’s location provides challenges. The Tongass National Forest, the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world, and the Tlingit Native villages, home to thousands of indigenous Alaskans, face threats from development and climate change, creating a uniquely complex setting in which to build.

While the students were there to gather information for their proposals, they also enmeshed themselves in the local community through service projects that included constructing a smokehouse.

“The students were amazing,” Tsien says. “They immediately got to work drawing up framing plans, making cutting diagrams, laying out boards, and nailing everything together. It was a complete scramble, but it came together perfectly. I was so proud.”

Tsien says that her students’ commitment to collaboration over competition epitomizes the way she thinks about architecture education.

“We spoke with leaders from the Tlingit tribe who helped us understand how they see the world and its interconnectedness,” Tsien says. “A person is related to a raven, is related to a fish, is related to the moss, is related to the bull kelp. We are all at the same level, and all have a responsibility to care for each other. This way of thinking really resonates with me and how I think of myself, my students, and my community.”

A Welcoming Environment

Tsien’s success as an architect could make her an intimidating professor, but her students are remarkably relaxed with her. Tsien jokes that it is hard to be intimidating once you have spent a week brushing your teeth together in the same freezing cold bathroom, but students credit her with fostering an intentionally warm environment.

“She really listens to us and works to help us become the best versions of ourselves, rather than molding our work to a preconceived idea,” says Tini Tang ’24 M.Arch. “She takes the time to look at our work from our perspective, which is incredibly unique in architecture education, where professors at other institutions often instead just provide feedback on projects based on how they would approach them.”

That culture of respect and collaboration is central to Tsien’s teaching philosophy.

“I don’t think that you can learn anything when you’re trying not to cry,” Tsien says. “For many years, architecture students would present their projects in front of juries who could be quite cruel, just ripping apart a project. I always hated that, because it was more about the juror posturing than trying to help a student learn. I am grateful that at Yale, we do things differently.”

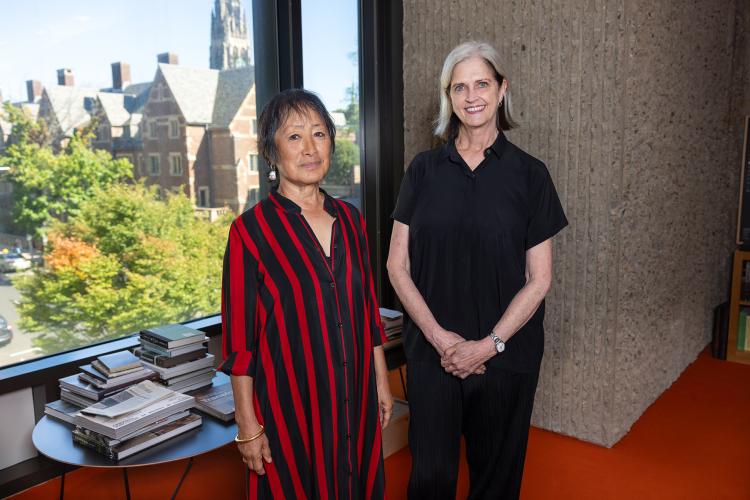

YSoA Dean Deborah Berke says Tsien’s teaching ethos makes her a perfect fit at Yale, as does her commitment to expanding accessibility.

“Efforts to increase financial aid are at the forefront of my work as dean,” Berke says. “I am so grateful to Tod for establishing this scholarship in Billie’s name. It will make a big difference in ensuring that the most qualified applicants can attend YSoA, regardless of their financial circumstances.”